Peter Mousaferiadis is facilitating the panel ‘Inclusive Innovation: Designing Tech for Diverse Societies in a Polarised Age’ at Tech Show Paris with some of the world’s thought leaders on inclusion for a paradigm-shifting conversation to investigate how human identity intersects with technology! Registration is free but you need to show up in person as these sessions are not livestreamed.

With: Gold Darr-Hood, Jean-Christophe Bas, Waqas Ahmed, Fadzi Whande

When: 11.25–12.15, 5 November

Where: Main Stage, Paris Expo, Porte de Versailles

Register here

‘Perhaps some balance will be established whereby the constant intermingling of individuals will be redeemed by the small number of individuals who will retain the capacity to feel Diversity.’

Victor Segalen, 1918

The Homogenising Effects of Deracination

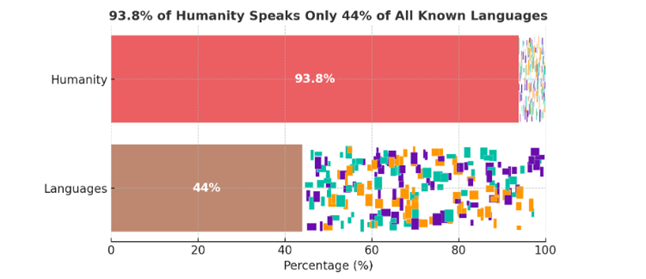

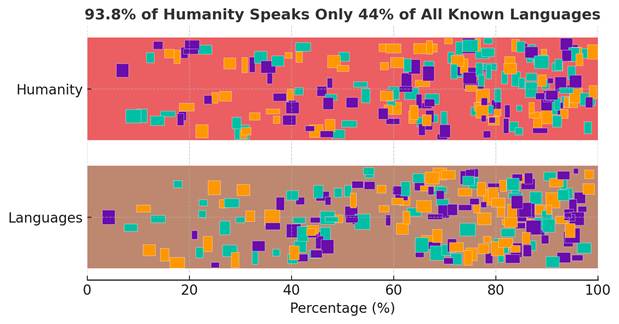

Indigenous people are believed to make up about 6.2% of the global population, representing about 476 million people, 90 countries and more than 4,000 languages.

Ethnologue counts a global total of 7,159 spoken languages, making up 56% of known languages. In other words, 93.8% of humanity speaks only 44% of all known languages.

Using language in this instance as a proxy for culture, this stark imbalance shows how cultural diversity is concentrated in the Indigenous population. It also shows the homogenising effects of deracination, i.e. loss of indigenous roots.

Unfortunately, homogenisation does not mean we all get along splendidly with each other. In fact, as historian Patrick Wolfe wrote, ‘to homogenise is to divide’. Why? Because the pressure to assimilate, abandoning one’s ancestral languages and norms, leads to misunderstandings, resentment, feelings of oppression and conflict.

And, in Patrick Wolfe’s words, ‘When insurgent classifications misguidedly seek to promote unworkable solidarities through obfuscating or homogenising away the different historical experiences that underlie ethno-racial specificity, they recapitulate assimilationism (which, after all, is an erasure of difference).’[1]

In a workplace context, for instance, a woman may feel pressured to conform to male standards by ignoring or medicating to overcome physical demands of menstruation, pregnancy or breastfeeding. Or a person who abstains from alcohol, especially for religious reasons, may feel excluded from work social events where everyone is expected to drink.

The pressures of assimilation often set up painful internal conflicts within individuals who want to fit in with their family and community, by, say, dressing according to their culture’s traditions, but also with mainstream society by adopting a ‘professional look’ that excludes many cultural expressions. These pressures can also lead to intergenerational conflicts within families.

On 3 September, my organisation, Cultural Infusion, hosted a book talk for my peer Gloria Tabi, author of Enough, who campaigns for acceptance of natural Afro hair after her experience over decades of wearing wigs due to her experience of hair discrimination.

Gloria’s compelling story is part of a broad shift in mainstream awareness of the toll that the pressure to assimilate has taken on individuals and on society. As Gloria says of this pressure, ‘The impact is overwhelming.’

‘We are all indigenous to the earth,’ is a phrase many people are familiar with, but what does it mean for the 93.8% of us who lost daily connection to a specific ancestral territory?

Even if we retain ancestral customs and languages, are we not (to varying degrees) shoehorned into a homogenising standard that rubs away infinitely precious cultural differences and alienates us from our own humanity?

What Do We Mean by ‘Inclusion’ and ‘Diversity’?

Too often we don’t know what we mean when we talk about inclusion and diversity. We use overly broad categories that ‘promote unworkable solidarities’. The power and reach of technology too often amplify our knowledge gaps.

If we are not building technology to include everyone in their specificity, we risk everything: our social cohesion and our humanity.

The only workable solidarity is one with the whole human race in our specificities.

God Is in the Detail

I wanted to build a platform that would help ensure that everyone was acknowledged and no one was left behind.

After leading a team of subject matter experts and developers over a period of more than seven years, this dream was realised in the form of Cultural Infusion’s Software-as-a-Service platform Atlas, previously known as Diversity Atlas.

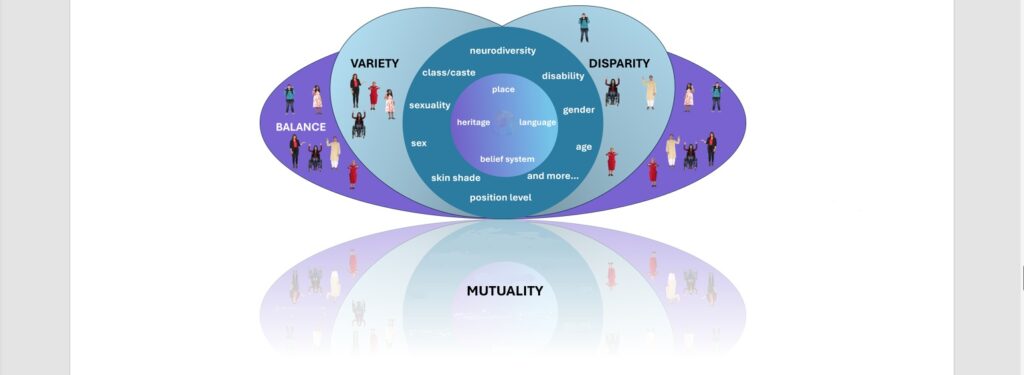

To create the platform, we needed to create a functional, measurable definition of cultural diversity. This definition can be represented by the following diagram:

The definition of cultural diversity represented by this diagram is a work-in-progress. It was created for a technical paper for UNESCO’s World Conference on Cultural Policies and Sustainable Development, Mondiacult 2025, where I am also delivering a talk on 30 September.

Underpinning the model is my insistence that every category be as inclusive as possible. This entailed collating a vast ‘Global Database of Humanity’. Our database contains more than 45,000 cultural attributes, including every known (to us): nation plus many culturally distinct regions; heritage[2]; language, dialect and speech group; and secular and secular-like belief system.

I am hoping this model will encourage lively discussion. We constantly learn and we do this work in community as we seek global solutions for our global problems.

There’s No Such Thing as Non-Indigenous

Palawa Elder Auntie Gabby tells me, ‘There’s no such thing as non-Indigenous. There’s no such thing as a non-person.’

So, let’s return to the diagram I shared earlier. It was a big exaggeration of the distinction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Auntie Gabby is right; it’s a false binary – which is not to discount the importance of this binary in determining and recognising Indigenous rights. We accept this as an unavoidable paradox.

The reality may be more accurately represented by something like this:

In this diagram, those closest to 100% speak their ancestral language, live on their ancestral lands, practise their ancestral customs and follow the beliefs of their ancestors over millennia. Those closest to 0% do not do any of the former and engage in space exploration with an intent to find habitat beyond our planet.

The Capacity to Feel Diversity

As we see the destructive effects of homogenisation on our societies and environments, we need to enhance our capacity to feel and embrace our diversity as the strength it is when not overlaid with fear of the so-called ‘other’.

If this conversation interests you, please add your voice and follow me on LinkedIn!

[1] Wolfe, Patrick, 2016. Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race. London: Verso.

[2] ‘racial, ethnic, religious, or cultural background’, as defined by the Cambridge Dictionary